More Muscle, Less Belly Fat: What Body Composition Tells Us About Brain Aging

Introduction: Brain Health Is Not Just in the Brain

When people think about protecting cognitive function as they age, the conversation usually centers on brain games, supplements, or genetics. But a growing body of research suggests that the brain does not age in isolation. The body it lives in matters—particularly muscle mass and visceral fat.

A 2025 study presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America adds important clarity to this conversation. Using whole-body MRI and artificial intelligence, researchers found that people with higher muscle mass and lower visceral fat relative to muscle had younger-looking brains, as measured by brain MRI–derived “brain age.”

This finding reinforces a key principle we emphasize at Zero Point One Physical Therapy: capacity in the body supports capacity in the brain. Strength, muscle mass, and metabolic health are not just orthopedic or aesthetic goals—they are neurological ones.

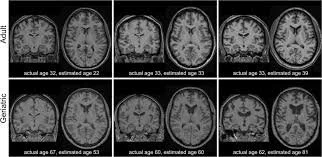

What Is “Brain Age” and Why Does It Matter?

Brain age is a computational estimate of how old a brain appears based on structural MRI features, compared to large reference datasets. When brain age exceeds chronological age, it has been associated with:

Higher risk of cognitive decline

Increased Alzheimer’s disease risk

Poorer overall brain health trajectories

Brain age is not a diagnosis. It is a biomarker—a signal that reflects how the brain has adapted to decades of lifestyle, metabolic, and health exposures.

The Study at a Glance

Primary source:

Raji C et al. More Muscle, Less Belly Fat Slows Brain Aging. RSNA Annual Meeting, 2025.

Participants

1,164 healthy adults

Mean age: 55.2 years

52 percent female

Four research sites

Methods

Whole-body MRI and brain MRI using T1-weighted sequences

AI-based quantification of:

Total normalized muscle volume

Visceral fat (deep abdominal fat around organs)

Subcutaneous fat (fat under the skin)

Brain age

Key Findings

A higher visceral fat–to–muscle ratio was associated with older brain age

Higher muscle mass was associated with younger brain age

Subcutaneous fat showed no significant relationship with brain age

In simple terms:

More muscle + less hidden belly fat = younger-looking brains

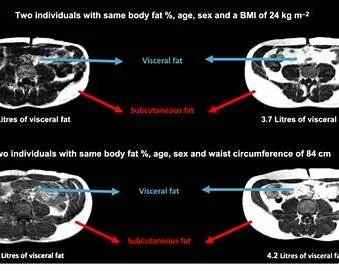

Why Visceral Fat Matters More Than Subcutaneous Fat

Not all fat behaves the same way biologically. Visceral fat is metabolically active and strongly linked to:

Chronic inflammation

Insulin resistance

Cardiovascular disease

Neurodegenerative risk

Subcutaneous fat, on the other hand, appears to be relatively benign in this context. This study found no meaningful association between subcutaneous fat and brain aging, reinforcing the idea that where fat is stored matters more than how much total fat someone carries.

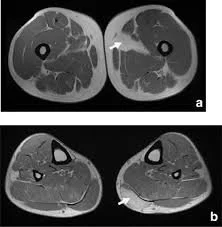

Muscle as a Marker of Brain Resilience

One of the most important takeaways from this study is the role of muscle mass as a surrogate marker of brain health.

Muscle is not just for movement. Skeletal muscle functions as an endocrine organ, influencing:

Glucose regulation

Inflammatory signaling

Blood flow and vascular health

Neurotrophic factors that support brain plasticity

Previous research has already linked sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss) to poorer cognitive outcomes and increased dementia risk (Moon et al., 2022; Chang et al., 2016). This study strengthens that link by showing a direct relationship between muscle volume and structural brain aging.

Exercise, Strength Training, and Brain Aging

This RSNA study was observational. It does not test exercise interventions directly. However, it strongly supports a growing consensus from interventional research:

Resistance training improves executive function and memory (Liu-Ambrose et al., 2010)

Combined aerobic and strength training slows cognitive decline (Northey et al., 2018)

Higher muscle strength is associated with lower dementia risk (Taekema et al., 2012)

Taken together, these findings suggest that training to build and preserve muscle is a foundational strategy for long-term brain health.

A Cautionary Note on Weight Loss Drugs

The authors also highlight an important and timely concern:

While GLP-1 medications such as semaglutide are effective for fat loss, they may also accelerate muscle loss if not paired with resistance training and adequate protein intake.

From a brain health perspective, losing visceral fat at the expense of muscle may blunt—or even reverse—some neurological benefits. The authors suggest that future therapies should aim to reduce visceral fat while preserving muscle mass, using MRI-based metrics to guide dosing and intervention design.

What This Means for Active Adults and Longevity

This study reinforces several principles we emphasize clinically:

Muscle is protective—for joints, metabolism, and now brain aging

Strength training is not optional if longevity and cognition matter

Body composition is a neurological issue, not just a fitness goal

Exercise programs should prioritize muscle preservation, especially during fat loss

At Zero Point One Physical Therapy, this aligns directly with our 3-step process:

Understand the Problem: Evaluate strength, capacity, and body composition trends

Rebuild the Foundation: Restore muscle and movement capacity

Raise the Ceiling: Build long-term resilience for performance and cognitive health

Related Reading from Zero Point One Physical Therapy

To deepen this conversation, explore these related articles on our site:

Muscle Mass Is the Currency of Functional Longevity

Metabolic Health, Movement, and Aging

Why Strength Training Matters More As You Age

Each expands on how muscle, metabolism, and movement capacity shape long-term health outcomes beyond pain relief.

Key Takeaways

Higher muscle mass and lower visceral fat are associated with a younger brain age

Visceral fat, not subcutaneous fat, is the primary driver of brain aging risk

Muscle loss may be an underappreciated risk factor for cognitive decline

Strength training is a brain health intervention, not just a physical one

Frequently Asked Questions: Muscle, Fat, and Brain Health

Does strength training really help brain health as we age?

Yes. Multiple studies show that resistance training improves cognitive function, executive processing, and memory while also lowering dementia risk. The recent RSNA research adds another layer by showing that higher muscle mass is associated with a younger brain age on MRI. In practical terms, building and maintaining muscle appears to support both physical and neurological resilience as we age.

Why is visceral fat worse for brain health than other types of fat?

Visceral fat is metabolically active and closely linked to inflammation, insulin resistance, and vascular disease. These factors negatively affect brain structure and function over time. The RSNA study found that visceral fat relative to muscle mass was associated with older brain age, while subcutaneous fat was not. This means where fat is stored matters more than total body weight when it comes to brain aging.

Can losing weight improve brain health?

Potentially, but how you lose weight matters. Fat loss that preserves or builds muscle appears most beneficial for brain health. Rapid weight loss without resistance training can lead to muscle loss, which may offset neurological benefits. For optimal brain aging outcomes, fat loss should be paired with strength training and adequate protein intake.

Do GLP-1 medications like Ozempic affect brain health?

There are popular theories—and emerging research—suggesting GLP-1 medications may indirectly influence brain health by improving metabolic markers. However, these medications can also lead to muscle loss if not carefully managed. Current evidence suggests that reducing visceral fat while preserving muscle is likely the best strategy for both body and brain health. Exercise and strength training remain critical regardless of medication use.

How much strength training do I need to support brain health?

Research generally supports 2–3 days per week of progressive resistance training, combined with aerobic activity, to improve cognitive outcomes. For busy NYC professionals, consistency matters more than perfection. Even short, well-structured strength sessions can meaningfully support muscle mass, metabolic health, and long-term brain resilience.

Is cardio or strength training better for brain health?

Both matter, but they work through different mechanisms. Aerobic exercise improves blood flow and cardiovascular health, while strength training preserves muscle mass and metabolic function. The best approach for brain health is a combination of both, with resistance training playing a larger role as we age.

At what age should I start strength training for brain health?

The earlier, the better—but it is never too late. Muscle loss and visceral fat accumulation typically accelerate after age 40, especially in sedentary adults. Starting strength training in your 30s or 40s can help slow brain aging, while starting later can still meaningfully improve function, independence, and cognitive resilience.

Can physical therapy help with brain health, or is it just for pain?

At Zero Point One Physical Therapy in NYC, physical therapy goes far beyond pain relief. A progressive, fitness-forward physical therapy program helps individuals rebuild muscle, improve metabolic health, and safely return to strength training—all of which support long-term brain health. For many active adults, PT is the bridge between pain and sustainable training.

How does this research apply to active adults in NYC specifically?

NYC professionals often face long work hours, high stress, and limited time to train. This research highlights that intentional strength training is not optional if longevity and brain health matter. Structured programs that build muscle while managing fatigue and recovery are especially important in high-demand urban lifestyles.

Where can I get help building muscle safely if I have pain or past injuries?

Working with a performance-based physical therapy clinic allows you to build muscle safely while addressing movement limitations, past injuries, and flare-up risk. This approach supports not only joint health and performance, but also long-term brain health through preserved muscle and reduced visceral fat.

If you are sick of being in pain and want to regain your freedom to live your fullest life, let us help you.

Book a FREE Phone Consult with Our Team.

Selected References

Raji C et al. RSNA Annual Meeting, 2025

Northey JM et al. Br J Sports Med. 2018

Liu-Ambrose T et al. Arch Intern Med. 2010

Chang KV et al. Eur Geriatr Med. 2016

Moon JH et al. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2022